Home > God at work in The Arts: Beauty, tradition & the work of our hands

God at work: The Arts

Beauty, tradition & the work of our hands

By Luke Sewell

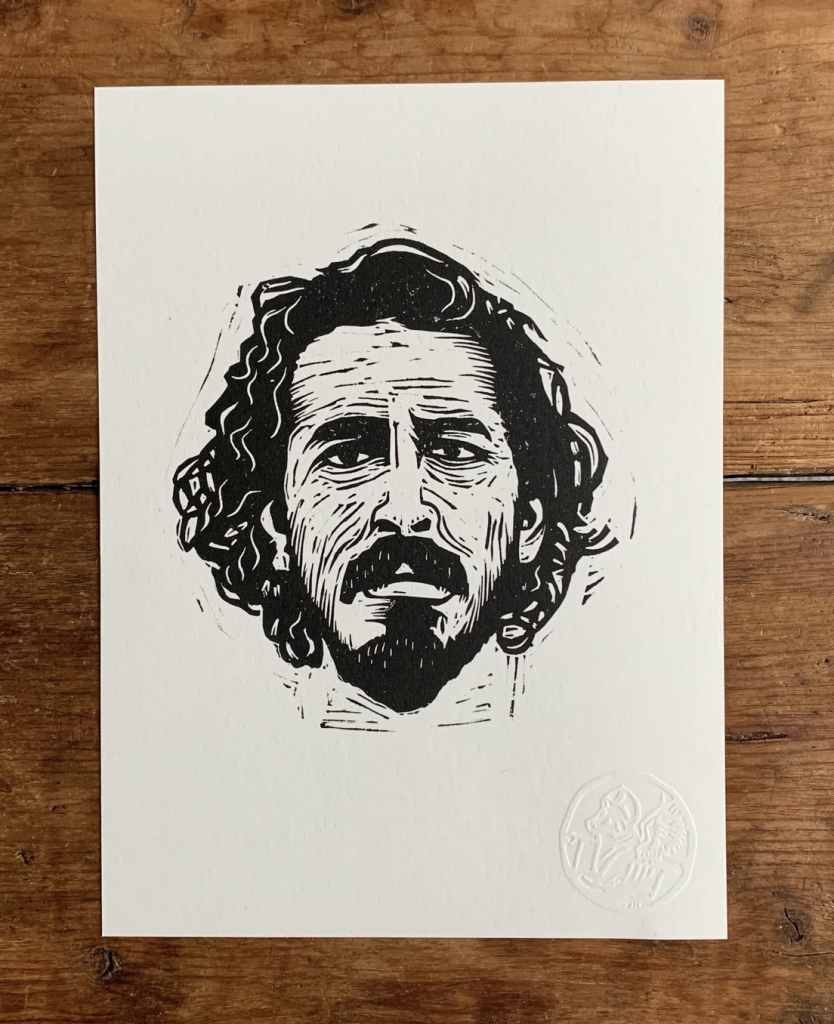

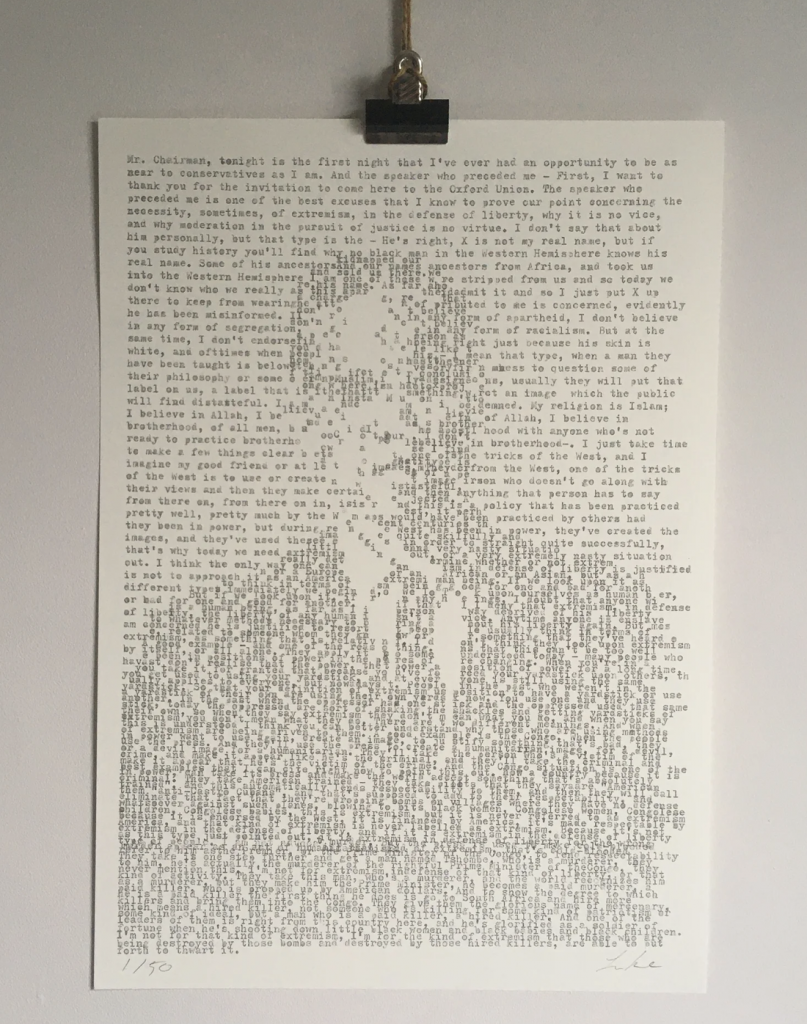

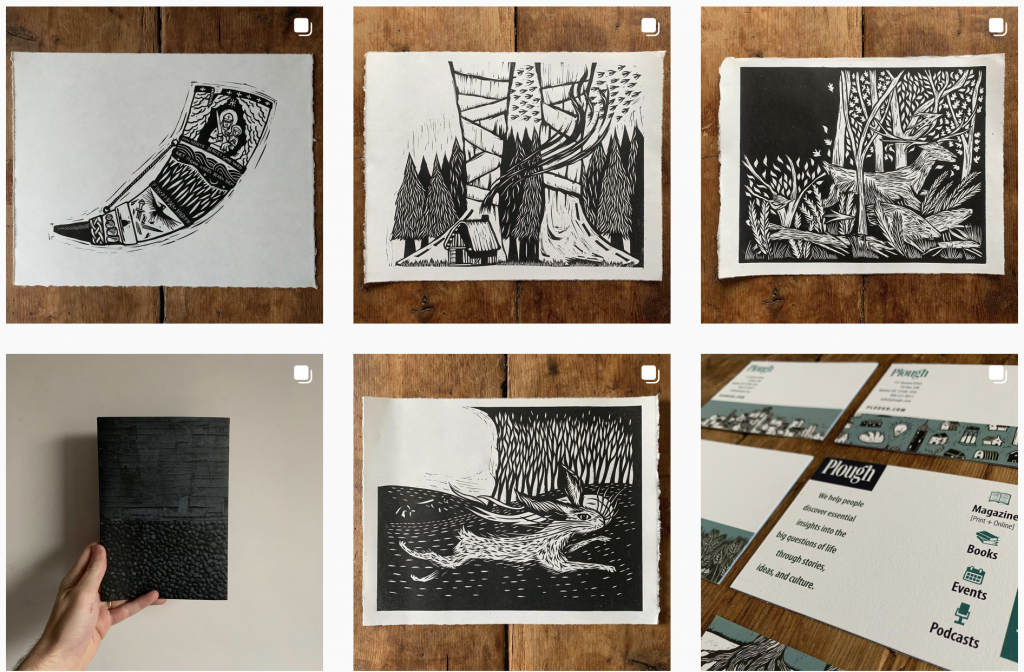

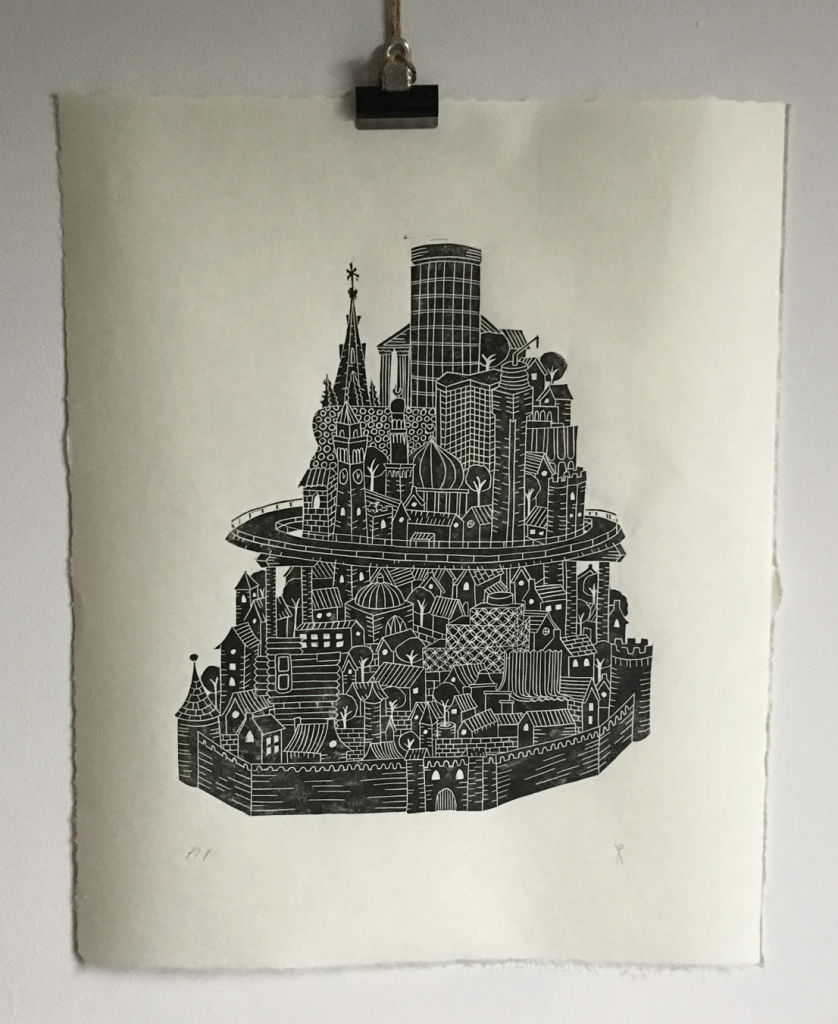

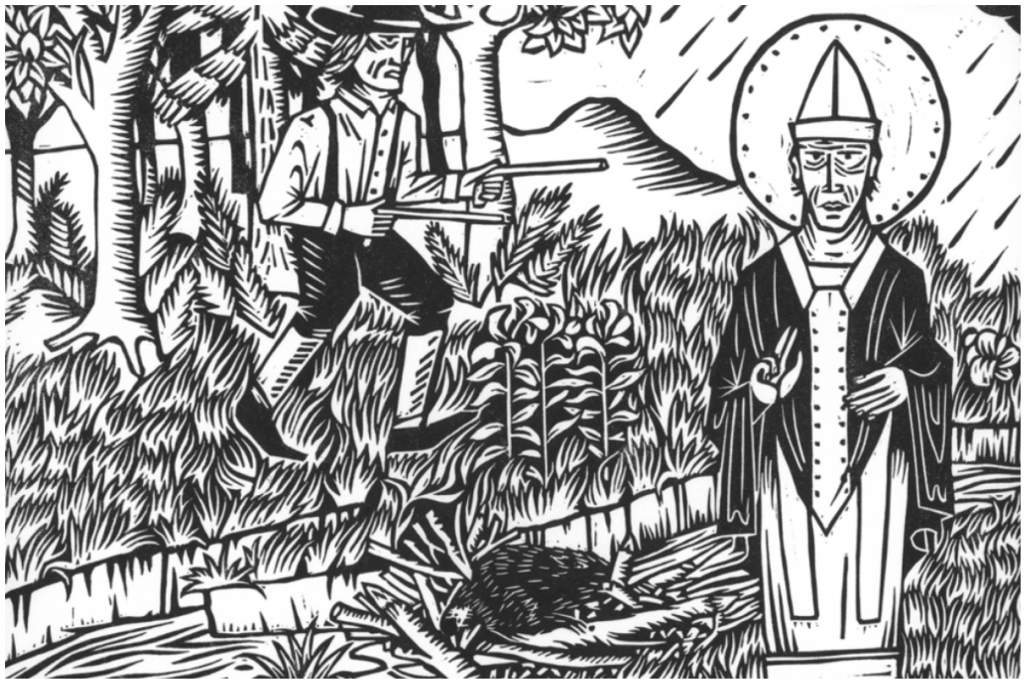

All images reference artwork by Luke Sewell. Find links below.

Every lunchtime, I say a midday prayer which begins with words from Psalm 90;

Let the beauty of the Lord our God be upon us,

Establish thou the work of our hands – establish thou the work of our hands.

Psalm 90 is one of my favourite psalms for lots of reasons. It possesses a beautiful melancholy that is in tune with the frailty of human life and the temptation to believe our work is meaningless, which helps counteract the sense that it is ourselves and the success of our endeavours that are at the centre of the world.

It also prioritises beauty as essential to our work, regardless of what we are putting our hands to – and recognises that beauty comes from God, something increasingly vital in an age where most of our labour has moved away from anything actually productive into the realm of speculation and exaggeration of reality. Psalm 90 invites us to reimagine work as something sacred.

I grew up in low church tradition that had long since done away with the idea of priests. Our church minister still did priestly things, but he was like the rest of us, wore regular clothes and hated being called ‘Reverend’.

This week we inducted a new priest at the parish church I attend in North Birmingham, where there are vestments as well as candles and a much more liturgical treatment of the Eucharist. Our priest was laden with heavy symbols and language setting her apart and indicating her authority and responsibility for the local community. But I came away from that service with the feeling that as a congregation we had somehow all been endowed with the same responsibility for seeking the cure of souls in the places where we work. Having a very visible priest invited us all to realise the heights of the truth that we are all ‘a royal priesthood …’.

From the age of 11 to 18 I attended a Grammar School which also encouraged its students to believe that we were a people set apart; in this case because we had passed an arbitrary test when we were 10 years old. We were led to aspire to attend a prestigious university and progress from there to an aspirational (and ideally high-paying) job.

I have never managed to find my way into one of those jobs, and a significant part of the almost 10 years since I graduated have been wasted apologising for that or feeling guilty about it; the sense that what I was doing wasn’t really a job, or that I was somehow abdicating the glorious purpose I had been endowed with in Year 6.

One of the most helpful ways of navigating this has been to view my weird collage of jobs (youth work, work in a bakery, museums collection management, picture framing and now, illustration) as vocation instead of a career. The value here is determined by what God wants me to do with my hands right now, instead of how much money I am earning or worse, attempting to coerce myself to a future goal based on income or status. I still find it hard to view illustration as a ‘job’, or ‘career’ and instead view it more like caring for my son – a sacred responsibility to be undertaken seriously and with care – something that can be a great deal of fun as well as requiring a lot of effort!

For many of us the past few years have exposed to a greater extent how much of our labour and consumer habits make us complicit, willingly or not, in enormous and seemingly inescapable systems that exploit and oppress others and take a significant toll on the Earth. A significant part of how I now understand my work isn’t directed towards productivity or even a sense of feeling fulfilled, but simply being able to authentically sound the cry of Psalm 90; “let the beauty of the Lord our God be upon us; establish thou the work of our hands.” If I can’t pray that with conviction, it’s possibly not a task worth doing. This doesn’t swap out the need for hard or mundane work – as we learnt during lockdown, and as I try to remember each time I change a nappy. Some of the jobs least appreciated by the market are actually the most essential, both to our communities and our own souls.

One of the prompts for this piece was to explain why the arts are important to God, a question that would be funny if it didn’t reflect the way that much of the Protestant tradition in the West has criticised and attacked cherished beliefs over the years. Art isn’t important in many of the ways modern life attributes importance – despite attempts to make art serve commerce or advertising, most art possesses little financial value and isn’t really looking to sell you anything anyway.

We worship a God who reveals Himself, or perhaps translates himself through art, be it the beautiful imagery and songs of the Scriptures, the created world, or what might at first appear to be a bizarre piece of participatory art; Communion, which many Christians still hold to be a real source of vitality, life and connection with the presence of God.

Western art’s most reproduced image happens to be the central image of our faith; of Christ crucified. It not only highlights the once-integral connection between the church and arts patronage, but also the value of images, symbolism and the imagination lifting our gaze from careers, money and even the work of our hands to something greater and more wondrous; a point so obvious to Catholic or Orthodox readers that it must sound stupid.

As to what that means practically to me as an illustrator at the moment, I’ve been working on some illustrations for Plough Quarterly over the last year or so. Plough is a publishing house and magazine that makes space for a range of thoughts on faith, arts and culture. They commissioned me to carve some linocuts illustrating the Kingdom of God. I’m also working on illustrations for GK Chesterton’s ‘Ballad of the White Horse’, a big poem about King Alfred which explores the fundamental differences between Christianity and nihilism. Musician and songwriter David Blower has also written a poem, and I’m beginning work on some drawings for that, too.

Isaiah 2:4 gives the impression that all our work is a rehearsal for the New Creation. My prayer is that at least some of my work will still exist there, fully glorified and redeemed, without that massive gap we all feel between our intention and our actions. That hope compels us to put our hands to the good work of beating swords into ploughshares and spears into pruning hooks now, today, wherever He has placed us.

Luke Sewell is a linoprint maker and illustrator living in Birmingham. He studied Archaeology and Ancient History as an undergraduate and completed a masters in Museum Curation, before going on to develop his artwork in linoprint, photography and illustration.

For more information about Luke’s artwork and ways to support him, visit:

https://www.lukeprints.co.uk/

https://www.patreon.com/lukeprints

https://www.instagram.com/lukeprints/

Talk to a Mentor

What hit home for you in this article? Would you like to discuss anything in particular?

Just fill in the form below and one of our mentors will get back to you as soon as possible.

Our mentors aren’t counsellors, but they are ordinary people willing to join others on their spiritual journey in a compassionate and respectful manner.